He had a profound impact on modern art of the 20th century. Always among the avant-garde, René Magritte was one of the leading figures of the Dada movement.

One day, he discovered a reproduction of a work by Chirico, Chant d’amour [The Song of Love]. A revelation. “My eyes saw thought for the first time,” he declared. The young Magritte was 24 years old. He had attended the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of Brussels as an unregistered student and had taken several courses before becoming a humble poster artist, the creator of paintings for decorative purposes.

Meeting those who were to become his Dada friends was a decisive moment in Magritte’s life. He dropped everything, or just about, quitting his job in a wallpaper factory. He became involved with several magazines, one of which was edited by Picabia, while pursuing his work as a painter and illustrator in an independent capacity.

However, this restricted lifestyle was not adventurous enough for him. He left Brussels for Paris, where he quickly made connections with the elite of the Surrealist movement, which had become the beating heart of literary, poetic and visual art creativity in Europe. This included André Breton, Max Ernst, Paul Éluard, but also Salvador Dalí who invited him to his home in Cadaqués, on the Catalan coast. Magritte painted. A lot. Recognition came fairly quickly in the 1930s. André Breton asked him to design the cover of his manifesto What is Surrealism? Galleries invited him to New York, London, to name but a few.

In the dark years of the Second World War, he became part of the Surrealist movement through his techniques derived from impressionism using the tips of his paintbrushes. He developed his own pictorial alphabet consisting of recurring motifs making his work unique.

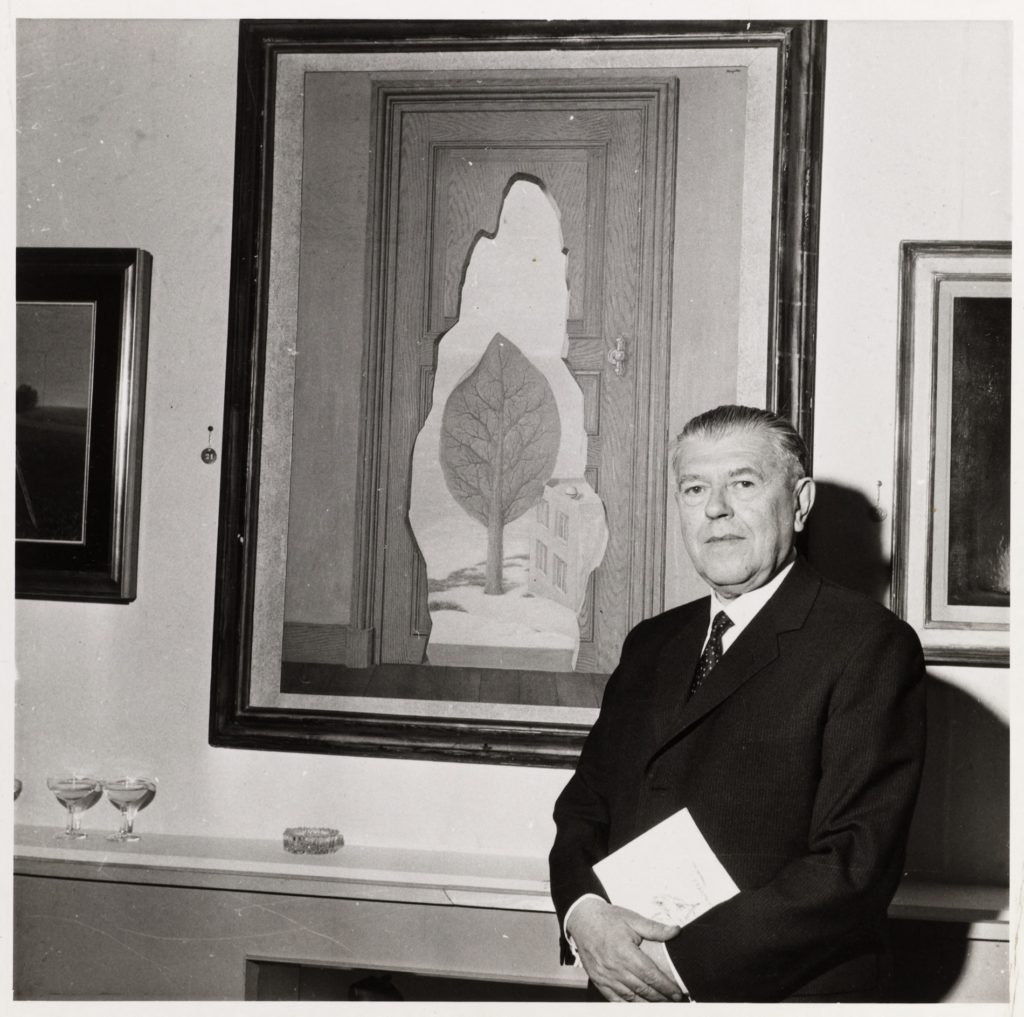

Immensely poetic, Magritte’s paintings consists of what one thinks are symbols but are rather the projection of a playful direct thought. Objects are at the centre of his work, such as the famous pipe, underlined with the phrase, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This Is Not a Pipe)”, which earned him worldwide recognition.

As for Champagne wine, it is not absent from the works and imaginary world of Magritte. A cloud rests on a champagne glass (La Corde sensible [Heartstring], 1960), a giraffe has slid into a glass flute (Le bain de cristal [The cut-glass bath], 1946). Magritte’s universe is limitless, heralding, to some extent, the pop art extravagance of the generation that followed. And precisely because he broke free from the codes of his era and was always able to remain at the forefront of creation, Magritte continues to question our own era through his work. As if his playful, quirky outlook on the world and the objects of our everyday life were still just as relevant today.